Back Ruimteverdrag Afrikaans معاهدة الفضاء الخارجي Arabic Tratáu sobre l'espaciu ultraterrestre AST Xarici Kosmos Müqaviləsi Azerbaijani Дагавор аб космасе Byelorussian Tractat de l'espai exterior Catalan Kosmická smlouva Czech Ydre rum-traktaten Danish Weltraumvertrag German Συνθήκη για το Εξωτερικό Διάστημα Greek

| Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies | |

|---|---|

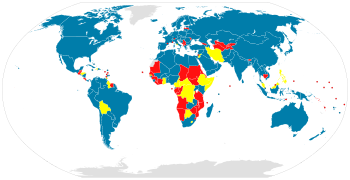

Parties Signatories Non-parties | |

| Signed | 27 January 1967 |

| Location | London, Moscow and Washington, D.C. |

| Effective | 10 October 1967 |

| Condition | 5 ratifications, including the depositary Governments |

| Parties | 115[1][2][3][4] |

| Depositary | Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America |

| Languages | English, French, Russian, Spanish, Chinese and Arabic |

| Full text | |

The Outer Space Treaty, formally the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, is a multilateral treaty that forms the basis of international space law. Negotiated and drafted under the auspices of the United Nations, it was opened for signature in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union on 27 January 1967, entering into force on 10 October 1967. As of March 2024[update], 115 countries are parties to the treaty—including all major spacefaring nations—and another 22 are signatories.[1][5][6]

The Outer Space Treaty was spurred by the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the 1950s, which could reach targets through outer space.[7] The Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in October 1957, followed by a subsequent arms race with the United States, hastened proposals to prohibit the use of outer space for military purposes. On 17 October 1963, the U.N. General Assembly unanimously adopted a resolution prohibiting the introduction of weapons of mass destruction in outer space. Various proposals for an arms control treaty governing outer space were debated during a General Assembly session in December 1966, culminating in the drafting and adoption of the Outer Space Treaty the following January.[7]

Key provisions of the Outer Space Treaty include prohibiting nuclear weapons in space; limiting the use of the Moon and all other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes; establishing that space shall be freely explored and used by all nations; and precluding any country from claiming sovereignty over outer space or any celestial body. Although it forbids establishing military bases, testing weapons and conducting military maneuvers on celestial bodies, the treaty does not expressly ban all military activities in space, nor the establishment of military space forces or the placement of conventional weapons in space.[8][9] From 1968 to 1984, the OST gave birth to four additional agreements: rules for activities on the Moon; liability for damages caused by spacecraft; the safe return of fallen astronauts; and the registration of space vehicles.[10]

OST provided many practical uses and was the most important link in the chain of international legal arrangements for space from the late 1950s to the mid-1980s. OST was at the heart of a 'network' of inter-state treaties and strategic power negotiations to achieve the best available conditions for nuclear weapons world security. The OST also declares that space is an area for free use and exploration by all and "shall be the province of all mankind". Drawing heavily from the Antarctic Treaty of 1961, the Outer Space Treaty likewise focuses on regulating certain activities and preventing unrestricted competition that could lead to conflict.[7] Consequently, it is largely silent or ambiguous on newly developed space activities such as lunar and asteroid mining.[11][12][13] Nevertheless, the Outer Space Treaty is the first and most foundational legal instrument of space law,[14] and its broader principles of promoting the civil and peaceful use of space continue to underpin multilateral initiatives in space, such as the International Space Station and the Artemis Program.[15][16]

- ^ a b "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

UKwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

USwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

RUwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

unodacnwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ In addition, the Republic of China in Taiwan, which is currently recognized by 11 UN member states, ratified the treaty prior to the United Nations General Assembly's vote to transfer China's seat to the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1971.

- ^ a b c "Outer Space Treaty". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Shakouri Hassanabadi, Babak (30 July 2018). "Space Force and international space law". The Space Review. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Irish, Adam (13 September 2018). "The Legality of a U.S. Space Force". OpinioJuris. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Buono, Stephen (2 April 2020). "Merely a 'Scrap of Paper'? The Outer Space Treaty in Historical Perspective". Diplomacy and Statecraft. 31 (2): 350-372. doi:10.1080/09592296.2020.1760038. S2CID 221060714.

- ^ If space is ‘the province of mankind’, who owns its resources? Senjuti Mallick and Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan. The Observer Research Foundation. 24 January 2019. Quote 1: "The Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967, considered the global foundation of the outer space legal regime, […] has been insufficient and ambiguous in providing clear regulations to newer space activities such as asteroid mining." *Quote2: "Although the OST does not explicitly mention "mining" activities, under Article II, outer space including the Moon and other celestial bodies are "not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty" through use, occupation or any other means."

- ^ Szoka, Berin; Dunstan, James (1 May 2012). "Law: Is Asteroid Mining Illegal?". Wired. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- ^ Who Owns Space? US Asteroid-Mining Act Is Dangerous And Potentially Illegal. IFL. Accessed on 9 November 2019. Quote 1: "The act represents a full-frontal attack on settled principles of space law which are based on two basic principles: the right of states to scientific exploration of outer space and its celestial bodies and the prevention of unilateral and unbriddled commercial exploitation of outer-space resources. These principles are found in agreements including the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and the Moon Agreement of 1979." *Quote 2: "Understanding the legality of asteroid mining starts with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. Some might argue the treaty bans all space property rights, citing Article II."

- ^ "Space Law". www.unoosa.org. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "International Space Station legal framework". www.esa.int. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "NASA: Artemis Accords". NASA. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search