Back Vitamien B12 Afrikaans فيتامين بي 12 Arabic B12 vitamini Azerbaijani ویتامین ب۱۲ AZB Bitamina B12 BCL Витамин B12 Bulgarian विटामिन बी12 Bihari Vitamin B12 BS Vitamina B₁₂ Catalan ڤیتامین بی ۱۲ CKB

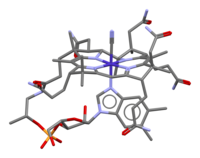

General skeletal formula of cobalamins | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vitamin B12, vitamin B-12, cobalamin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605007 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, intravenous (IV), intramuscular (IM), intranasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Readily absorbed in distal half of the ileum. |

| Protein binding | Very high to specific transcobalamins plasma proteins. Binding of hydroxocobalamin is slightly higher than cyanocobalamin. |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | Approximately 6 days (400 days in the liver). |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C63H88CoN14O14P |

| Molar mass | 1355.388 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in metabolism.[2] It is one of eight B vitamins. It is required by animals, which use it as a cofactor in DNA synthesis, and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism.[3] It is important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin, and in the circulatory system in the maturation of red blood cells in the bone marrow.[2][4] Plants do not need cobalamin and carry out the reactions with enzymes that are not dependent on it.[5]

Vitamin B12 is the most chemically complex of all vitamins,[6] and for humans the only vitamin that must be sourced from animal-derived foods or supplements.[2][7] Only some archaea and bacteria can synthesize vitamin B12.[8] Vitamin B12 deficiency is a widespread condition that is particularly prevalent in populations with low consumption of animal foods. This can be due to a variety of reasons, such as low socioeconomic status, ethical considerations, or lifestyle choices such as veganism.[9]

Foods containing vitamin B12 include meat, shellfish, liver, fish, poultry, eggs, and dairy products.[2] Many breakfast cereals are fortified with the vitamin.[2] Supplements and medications are available to treat and prevent vitamin B12 deficiency.[2] They are usually taken by mouth, but for the treatment of deficiency may also be given as an intramuscular injection.[2][6]

Vitamin B12 deficiencies have a greater effect on the pregnant, young children, and elderly people, and are more common in middle and lower developed countries due to malnutrition.[10] The most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency in developed countries is impaired absorption due to a loss of gastric intrinsic factor (IF) which must be bound to a food-source of B12 in order for absorption to occur.[11] A second major cause is an age-related decline in stomach acid production (achlorhydria), because acid exposure frees protein-bound vitamin.[12] For the same reason, people on long-term antacid therapy, using proton-pump inhibitors, H2 blockers or other antacids are at increased risk.[13]

The diets of vegetarians and vegans may not provide sufficient B12 unless a dietary supplement is taken.[2] A deficiency may be characterized by limb neuropathy or a blood disorder called pernicious anemia, a type of anemia in which red blood cells become abnormally large.[2] This can result in fatigue, decreased ability to think, lightheadedness, shortness of breath, frequent infections, poor appetite, numbness in the hands and feet, depression, memory loss, confusion, difficulty walking, blurred vision, irreversible nerve damage, and many others.[14] If left untreated in infants, deficiency may lead to neurological damage and anemia.[2] Folate levels in the individual may affect the course of pathological changes and symptomatology of vitamin B12 deficiency. Vitamin B12 deficiency in pregnant women is strongly associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, congenital malformations such as neural tube defects, problems with brain development growth in the unborn child.[10]

Vitamin B12 was discovered as a result of pernicious anemia, an autoimmune disorder in which the blood has a lower than normal number of red blood cells, due to a deficiency of vitamin B12.[5][15] The ability to absorb the vitamin declines with age, especially in people over 60.[16]

- ^ Prieto T, Neuburger M, Spingler B, Zelder F (2016). "Inorganic Cyanide as Protecting Group in the Stereospecific Reconstitution of Vitamin B12 from an Artificial Green Secocorrinoid" (PDF). Org. Lett. 18 (20): 5292–5295. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02611. PMID 27726382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Office of Dietary Supplements (6 April 2021). "Vitamin B12: Fact Sheet for Health Professionals". Bethesda, Maryland: US National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2021-10-08. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ Yamada K (2013). "Cobalt: Its Role in Health and Disease". In Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RK (eds.). Interrelations between Essential Metal Ions and Human Diseases. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 13. Springer. pp. 295–320. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_9. ISBN 978-94-007-7499-5. PMID 24470095.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Calderon2020was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Smith2019was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Vitamin B12". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. 4 June 2015. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Vincenti A, Bertuzzo L, Limitone A, D'Antona G, Cena H (June 2021). "Perspective: Practical Approach to Preventing Subclinical B12 Deficiency in Elderly Population". Nutrients. 13 (6): 1913. doi:10.3390/nu13061913. PMC 8226782. PMID 34199569.

- ^ Watanabe F, Bito T (January 2018). "Vitamin B12 sources and microbial interaction". Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 243 (2): 148–158. doi:10.1177/1535370217746612. PMC 5788147. PMID 29216732.

- ^ Obeid R, Heil SG, Verhoeven MM, van den Heuvel EG, de Groot LC, Eussen SJ (2019). "Vitamin B12 Intake From Animal Foods, Biomarkers, and Health Aspects". Front Nutr. 6: 93. doi:10.3389/fnut.2019.00093. PMC 6611390. PMID 31316992.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

PKIN2020VitB12was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

DRItextwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Acid-Reflux Drugs Tied to Lower Levels of Vitamin B-12". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-07-23.

- ^ "Vitamin B12 Deficiency Anemia". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 8 August 2021. Retrieved 2022-02-16.

- ^ "Pernicious anemia: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ Baik HW, Russell RM (2021-11-18). "Vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly". Annual Review of Nutrition. 19: 357–377. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.357. PMID 10448529.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search