Back معالجة الجفاف عن طريق الفم Arabic মৌখিক পুনরুদন থেরাপি Bengali/Bangla Sals de rehidratació oral Catalan Rehydratační roztok Czech WHO-Trinklösung German Sales de rehidratación oral Spanish او آر اس Persian Oraalinen nestehoito Finnish Soluté de réhydratation orale French मौखिक पुनर्जलीकरण चिकित्सा Hindi

| Oral rehydration therapy | |

|---|---|

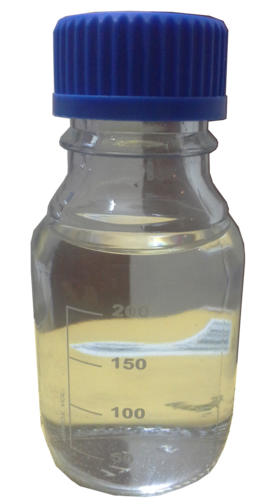

An oral rehydration solution (250ml) prepared according to WHO formula. | |

| Other names | oral rehydration solution (ORS), oral rehydration salts (ORS), glucose-salt solution |

Oral rehydration therapy (ORT) is a type of fluid replacement used to prevent and treat dehydration, especially due to diarrhea.[1] It involves drinking water with modest amounts of sugar and salts, specifically sodium and potassium.[1] Oral rehydration therapy can also be given by a nasogastric tube.[1] Therapy can include the use of zinc supplements to reduce the duration of diarrhea in infants and children under the age of 5.[1] Use of oral rehydration therapy has been estimated to decrease the risk of death from diarrhea by up to 93%.[2]

Side effects may include vomiting, high blood sodium, or high blood potassium.[1] If vomiting occurs, it is recommended that use be paused for 10 minutes and then gradually restarted.[1] The recommended formulation includes sodium chloride, sodium citrate, potassium chloride, and glucose.[1] Glucose may be replaced by sucrose and sodium citrate may be replaced by sodium bicarbonate, if not available, although the resulting mixture is not shelf stable in high-humidity environments.[1][3] It works as glucose increases the uptake of sodium and thus water by the intestines, and the potassium chloride and sodium citrate help prevent hypokalemia and acidosis, respectively, which are both common side effects of diarrhea.[4][3][5] A number of other formulations are also available including versions that can be made at home.[4][2] However, the use of homemade solutions has not been well studied.[2]

Oral rehydration therapy was developed in the 1940s using electrolyte solutions with or without glucose on an empirical basis chiefly for mild or convalescent patients, but did not come into common use for rehydration and maintenance therapy until after the discovery that glucose promoted sodium and water absorption during cholera in the 1960s.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] Globally, as of 2015[update], oral rehydration therapy is used by 41% of children with diarrhea.[8] This use has played an important role in reducing the number of deaths in children under the age of five.[8]

- ^ a b c d e f g h World Health Organization (2009). Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR (eds.). WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization (WHO). pp. 349–351. hdl:10665/44053. ISBN 9789241547659.

- ^ a b c Munos MK, Walker CL, Black RE (April 2010). "The effect of oral rehydration solution and recommended home fluids on diarrhoea mortality". International Journal of Epidemiology. 39 (Suppl 1): i75–87. doi:10.1093/ije/dyq025. PMC 2845864. PMID 20348131.

- ^ a b Islam MR (1986). "Citrate can effectively replace bicarbonate in oral rehydration salts for cholera and infantile diarrhoea". Bull World Health Organ. 64 (1): 145–150. PMC 2490925. PMID 3015443.

- ^ a b Binder HJ, Brown I, Ramakrishna BS, Young GP (March 2014). "Oral rehydration therapy in the second decade of the twenty-first century". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 16 (3): 376. doi:10.1007/s11894-014-0376-2. PMC 3950600. PMID 24562469.

- ^ Nalin DR, Harland E, Ramlal A, Swaby D, McDonald J, Gangarosa R, Levine M, Akierman A, Antoine M, Mackenzie K, Johnson B (November 1980). "Comparison of low and high sodium and potassium content in oral rehydration solutions". J Pediatr. 97 (5): 848–853. doi:10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80287-3. PMID 7431183.

- ^ Selendy JM (2011). Water and Sanitation Related Diseases and the Environment: Challenges, Interventions and Preventive Measures. John Wiley & Sons. p. 60. ISBN 9781118148600. Archived from the original on 18 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b The State of the World's Children 2016 A fair chance for every child (PDF). UNICEF. June 2016. pp. 117, 129. ISBN 978-92-806-4838-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search