Back Lorentz-Transformation ALS تحويل لورينتز Arabic Пераўтварэнні Лорэнца Byelorussian Пераўтварэньні Лёрэнца BE-X-OLD Лоренцови трансформации Bulgarian লরেন্টজ রূপান্তর Bengali/Bangla Transformació de Lorentz Catalan Lorentzova transformace Czech Лоренц улшăвĕсем CV Lorentz-transformation Danish

| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

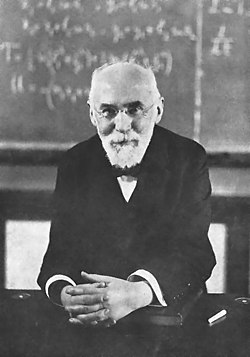

In physics, the Lorentz transformations are a six-parameter family of linear transformations from a coordinate frame in spacetime to another frame that moves at a constant velocity relative to the former. The respective inverse transformation is then parameterized by the negative of this velocity. The transformations are named after the Dutch physicist Hendrik Lorentz.

The most common form of the transformation, parametrized by the real constant representing a velocity confined to the x-direction, is expressed as[1][2] where (t, x, y, z) and (t′, x′, y′, z′) are the coordinates of an event in two frames with the spatial origins coinciding at t = t′ = 0, where the primed frame is seen from the unprimed frame as moving with speed v along the x-axis, where c is the speed of light, and is the Lorentz factor. When speed v is much smaller than c, the Lorentz factor is negligibly different from 1, but as v approaches c, grows without bound. The value of v must be smaller than c for the transformation to make sense.

Expressing the speed as a fraction of the speed of light, an equivalent form of the transformation is[3]

Frames of reference can be divided into two groups: inertial (relative motion with constant velocity) and non-inertial (accelerating, moving in curved paths, rotational motion with constant angular velocity, etc.). The term "Lorentz transformations" only refers to transformations between inertial frames, usually in the context of special relativity.

In each reference frame, an observer can use a local coordinate system (usually Cartesian coordinates in this context) to measure lengths, and a clock to measure time intervals. An event is something that happens at a point in space at an instant of time, or more formally a point in spacetime. The transformations connect the space and time coordinates of an event as measured by an observer in each frame.[nb 1]

They supersede the Galilean transformation of Newtonian physics, which assumes an absolute space and time (see Galilean relativity). The Galilean transformation is a good approximation only at relative speeds much less than the speed of light. Lorentz transformations have a number of unintuitive features that do not appear in Galilean transformations. For example, they reflect the fact that observers moving at different velocities may measure different distances, elapsed times, and even different orderings of events, but always such that the speed of light is the same in all inertial reference frames. The invariance of light speed is one of the postulates of special relativity.

Historically, the transformations were the result of attempts by Lorentz and others to explain how the speed of light was observed to be independent of the reference frame, and to understand the symmetries of the laws of electromagnetism. The transformations later became a cornerstone for special relativity.

The Lorentz transformation is a linear transformation. It may include a rotation of space; a rotation-free Lorentz transformation is called a Lorentz boost. In Minkowski space—the mathematical model of spacetime in special relativity—the Lorentz transformations preserve the spacetime interval between any two events. They describe only the transformations in which the spacetime event at the origin is left fixed. They can be considered as a hyperbolic rotation of Minkowski space. The more general set of transformations that also includes translations is known as the Poincaré group where initial time and initial origin coordinates of the two reference frames may differ, the two frames may have axes oriented differently and the direction of the speed between frames is arbitrary.

- ^ Rao, K. N. Srinivasa (1988). The Rotation and Lorentz Groups and Their Representations for Physicists (illustrated ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-470-21044-4. Equation 6-3.24, page 210

- ^ Forshaw & Smith 2009

- ^ Cottingham & Greenwood 2007, p. 21

Cite error: There are <ref group=nb> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=nb}} template (see the help page).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search