Back Epikurus Afrikaans Epicuro AN إبيقور Arabic ابيكوروس ARZ Epicuru AST Epikür Azerbaijani Эпикур Bashkir Эпікур Byelorussian Епикур Bulgarian এপিকুরোস Bengali/Bangla

Epicurus | |

|---|---|

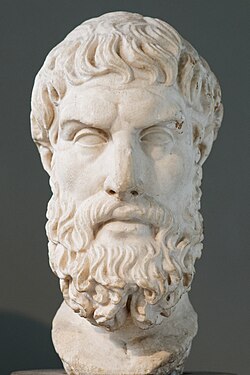

Roman marble bust of Epicurus | |

| Born | February 341 BC Samos, Greece |

| Died | 270 BC (aged about 72) Athens, Greece |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Epicureanism |

| Main interests | |

| Notable ideas | Attributed: |

Epicurus (/ˌɛpɪˈkjʊərəs/, EH-pih-KURE-əs;[2] Ancient Greek: Ἐπίκουρος Epikouros; 341–270 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher who founded Epicureanism, a highly influential school of philosophy that asserted that philosophy's purpose is to attain as well as to help others attain tranquil lives, characterized by freedom from fear and the absence of pain.

Epicurus advocated that people were best able to pursue philosophy by living a self-sufficient life surrounded by friends; he and his followers were known for eating simple meals and discussing a wide range of philosophical subjects at "the Garden", the school he established in Athens. Epicurus taught that although the gods exist, they have no involvement in human affairs. Like the earlier philosopher Democritus, Epicurus claimed that all occurrences in the natural world are ultimately the result of tiny, invisible particles known as atoms moving and interacting in empty space, though Epicurus also deviated from Democritus by proposing the idea of atomic "swerve", which holds that atoms may deviate from their expected course, thus permitting humans to possess free will in an otherwise deterministic universe.

Of the over 300 works said to have been written by Epicurus about various subjects, the vast majority have been lost. Only three letters written by him—the letters to Menoeceus, Pythocles, and Herodotus—and two collections of quotes—the Principal Doctrines and the Vatican Sayings—have survived intact, along with a few fragments of his other writings; most knowledge about his philosophy is due to later authors.

Epicureanism reached the height of its popularity during the late years of the Roman Republic, but by late antiquity, it had died out. Throughout the Middle Ages, Epicurus was popularly, though inaccurately, remembered as a patron of drunkards, whoremongers, and gluttons. His teachings gradually became more widely known in the fifteenth century with the rediscovery of important texts, but his ideas did not become acceptable until the seventeenth century, when the French Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi revived a modified version of them, which was promoted by other writers, including Walter Charleton and Robert Boyle. His influence grew considerably during and after the Enlightenment, profoundly impacting the ideas of major thinkers, including John Locke, Thomas Jefferson, Jeremy Bentham, and Karl Marx.

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search